Louvre.

There is no need to dwell too much on what is, without a doubt, the most famous museum in the world.

Described and represented in every possible way, the backdrop to many films, it has been cited in literature for as long as we can remember. Among all the books that celebrate the spaces and the incredible collections (how can you blame him), there is however a writer – a Parisian one at that – who in one of his works from 1877, transforms an episode at the Louvre into an indictment against the museum.

Who are we talking about?

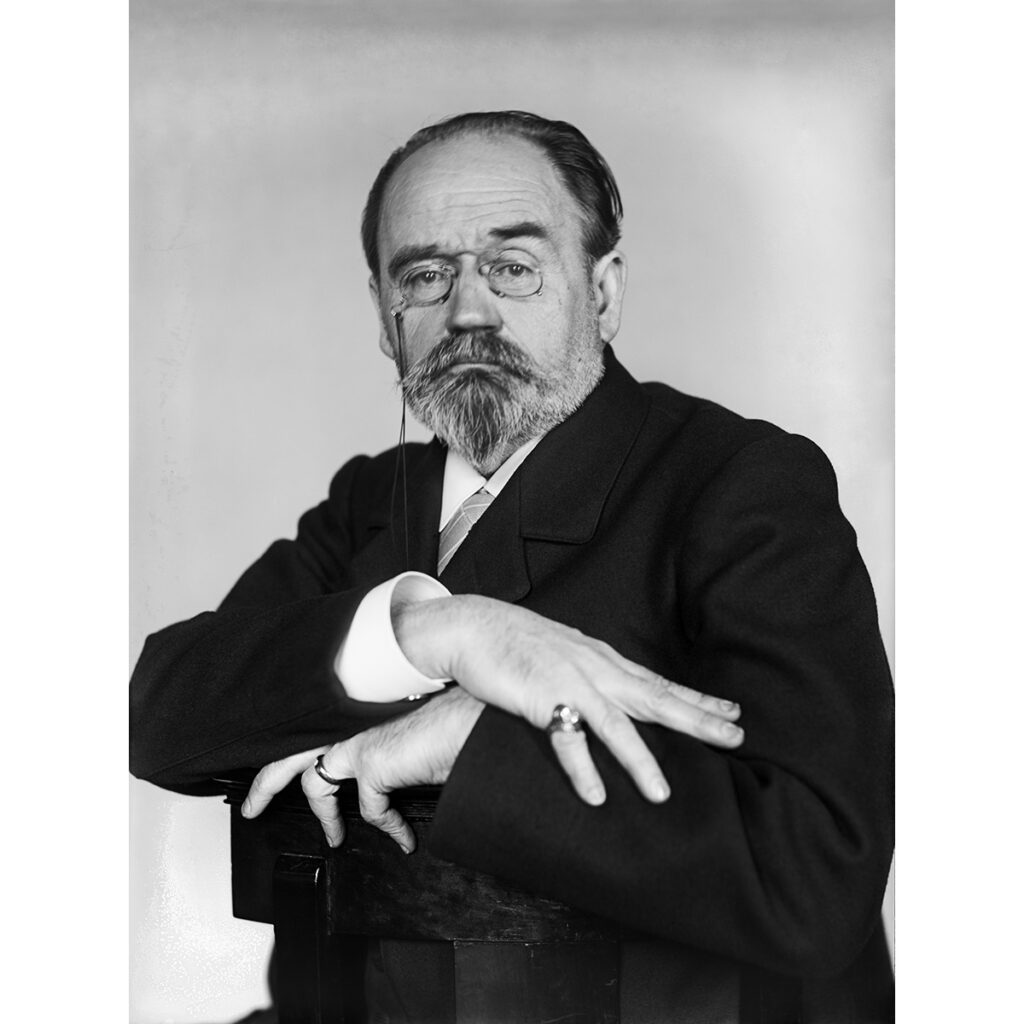

By Émile Zola, among the most appreciated French novelists, published, translated and commented on throughout the world. The book is the Assommoir,translates as come “The slaughterhouse” or “The slaughterhouse” and published for the first time in Italy in 1878, a year after its release in France.

The two protagonists, an engaged couple, Gervaise and Coupeau, unexpectedly find themselves with all their guests at the museum on their wedding day. So they begin their tour:

“Damn! it was cold in there! that room would have made an excellent cellar. And slowly the couples proceeded with their chins raised, blinking among the colossi, the stone, the black marble gods (…), the monstrous half-woman beasts with faces of death (…) they found everything very ugly. “

When the group continues in the other rooms, things certainly don’t improve. In front of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, “Coupeau stopped in front of the Mona Lisa, in which he found a resemblance to one of his aunts”.

The group continues their visit, trudging from one room to another, until they lose orientation and get lost. “seven or eight rooms away, deserted, cold, decorated only with severe noticeboards, where an innumerable quantity of broken piñatas and very ugly figurines were lined up.”

In the end they manage to leave the museum, exhausted and tired.

Zola against the museum

Émile Zola, Émile Zola, in his Assomoir, which is actually a much analyzed and commented piece, carries out a real invective not only against the Louvre, but in general against the institution it represents.

Zolahighlights how the public, despite recognizing its value and therefore going to visit it, then feels excluded and discriminated against by the messages that that museum conveys.

The Louvre, in Zola‘s pages, is a class separator that makes those who are unable to interpret its values inferior.

The question remains whether after more than a century, Zola‘s opinion is still relevant.